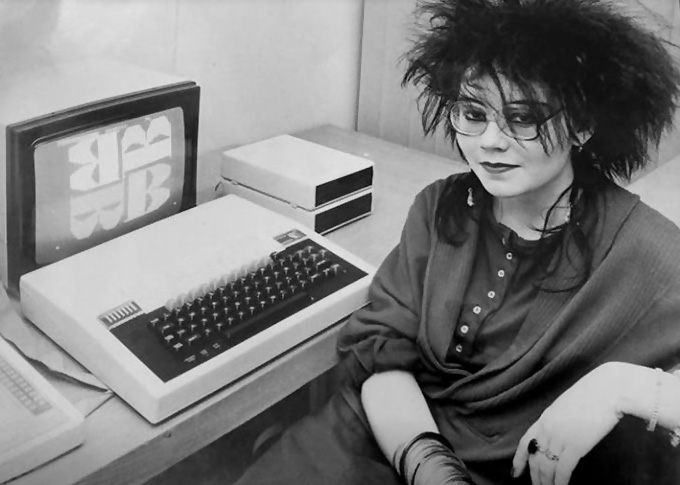

Developments in technology throughout the 1970s facilitated the growth of a phenomenon that would later be termed telematic art. Taking its name from telecommunications and informatics, this type of art utilises electronic communication networks for artistic collaboration.

Through telematic networks, our presence is distributed. We are both present and absent, here and elsewhere, all at the same time. It seems that embodied representation is giving way to disembodied reconstruction of ourselves.

Roy Ascott, Telematic Embrace, p351

Roy Ascott is regarded as a pioneer in the field of telematic art. His cross-continental piece Terminal Art (1980) was the first artists’ computer conferencing project between the UK and the USA, linking seven artists in California, New York, Massachusetts, San Francisco and Wales.

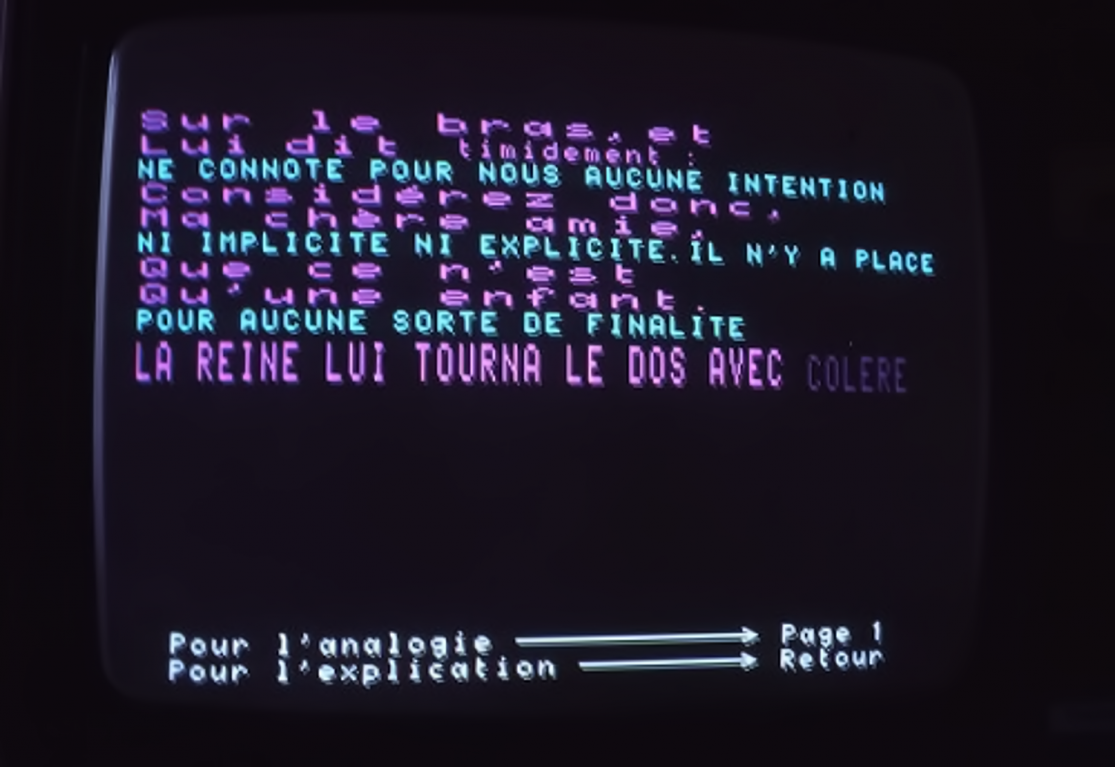

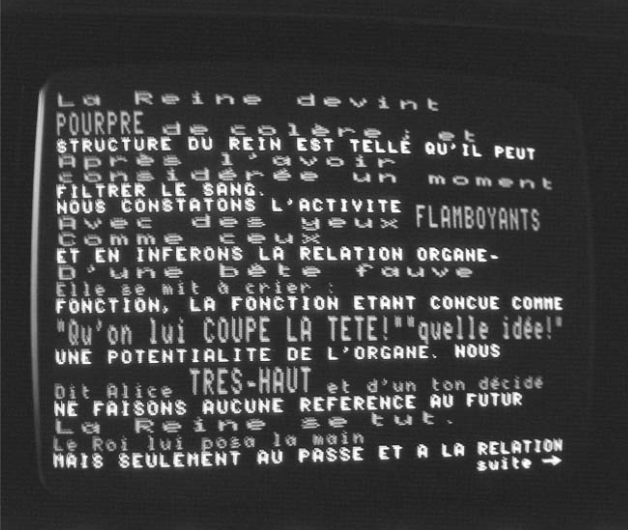

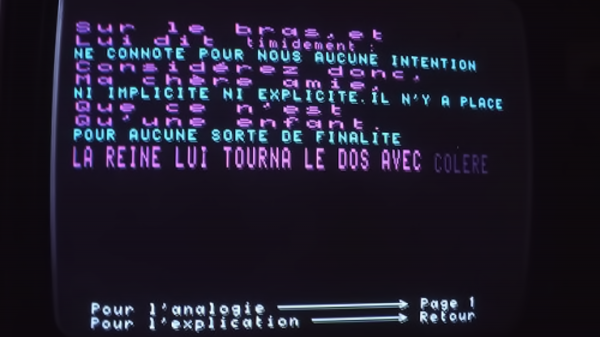

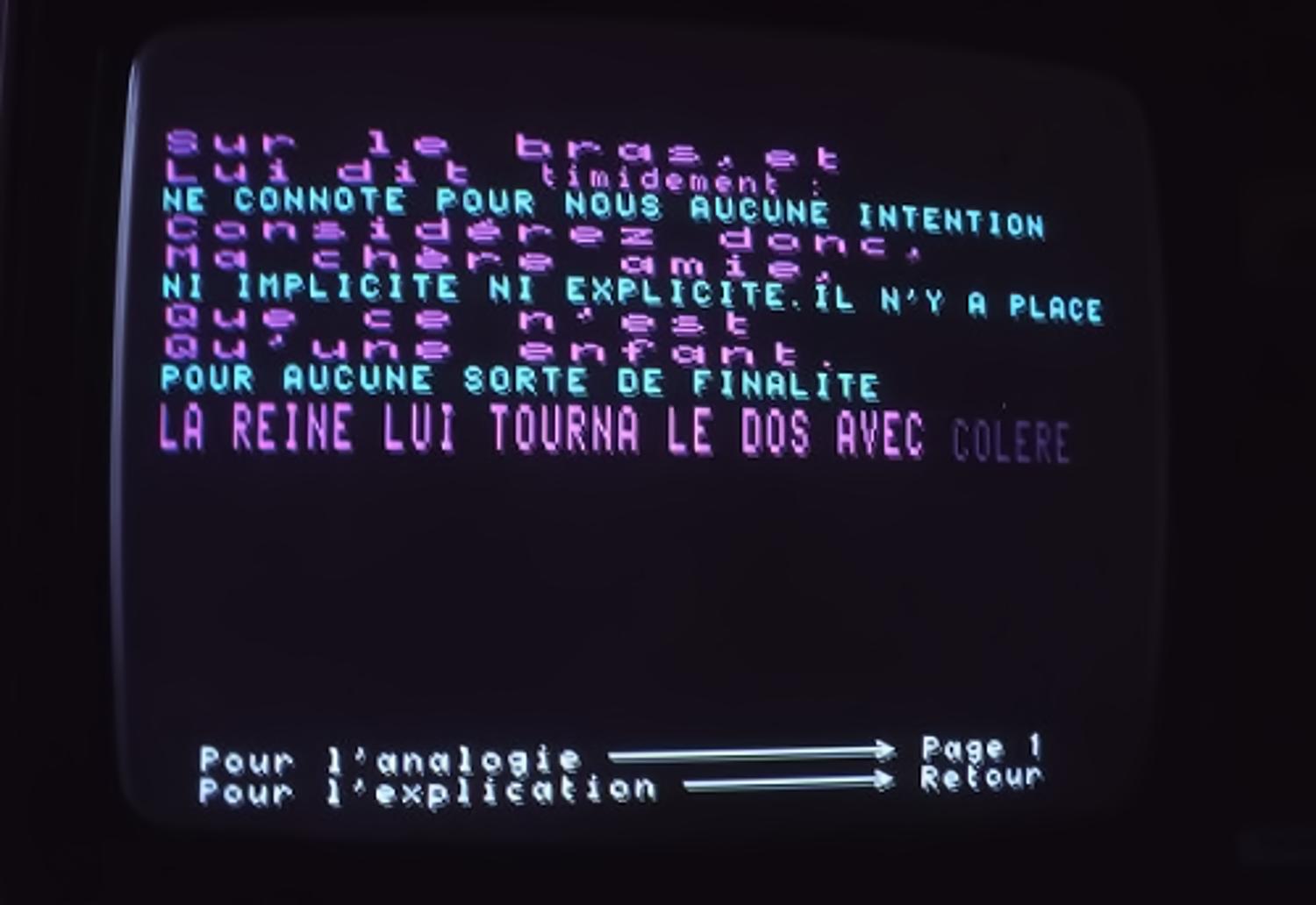

His 1985 piece Organe et Fonction d’Alice au Pays des Marvelles (for the exhibition Les Immateriaux) was even broader in scope, making use of French public videotex network Minitel. Randomly selected excerpts from the French translation of Alice in Wonderland were combined with the scientific treatise Organe et fonction to create a form of frequently serendipitous concrete poetry.

… The telematic project devised by Art Accès for the exhibition “Les Immatériaux” at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1985 … involved the use of the French national Minitel system as the network for on-line interaction between artists “in” the exhibition and the large population of Minitel subscribers distributed throughout the greater Paris region.

Roy Ascott, Telematic Embrace, p240

Telematic teletext art

Ascott sees participation, collaboration and communication as integral to telematic art. Unlike videotex systems such as Minitel and Prestel, teletext is one-way technology in that you can receive information but have no way of sending anything back. However, teletext is telematic in the broadest sense because it is broadcast via television, but it can also be interactive.

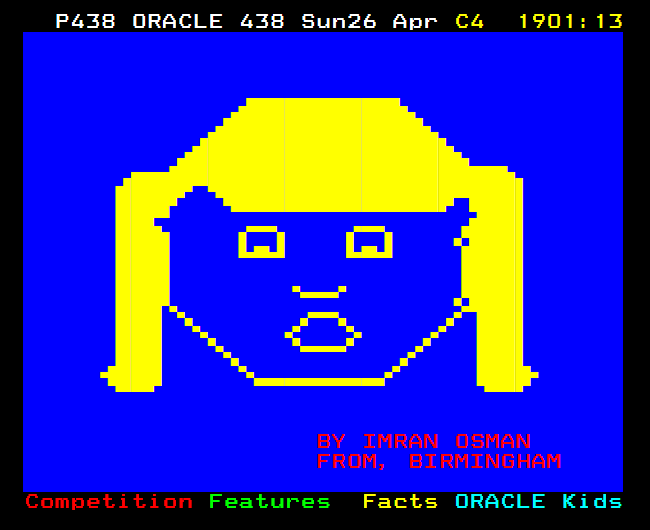

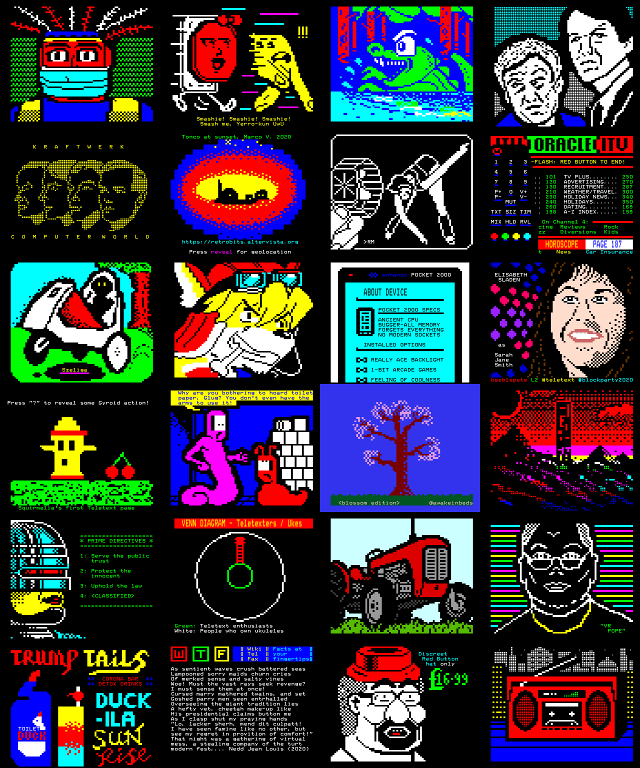

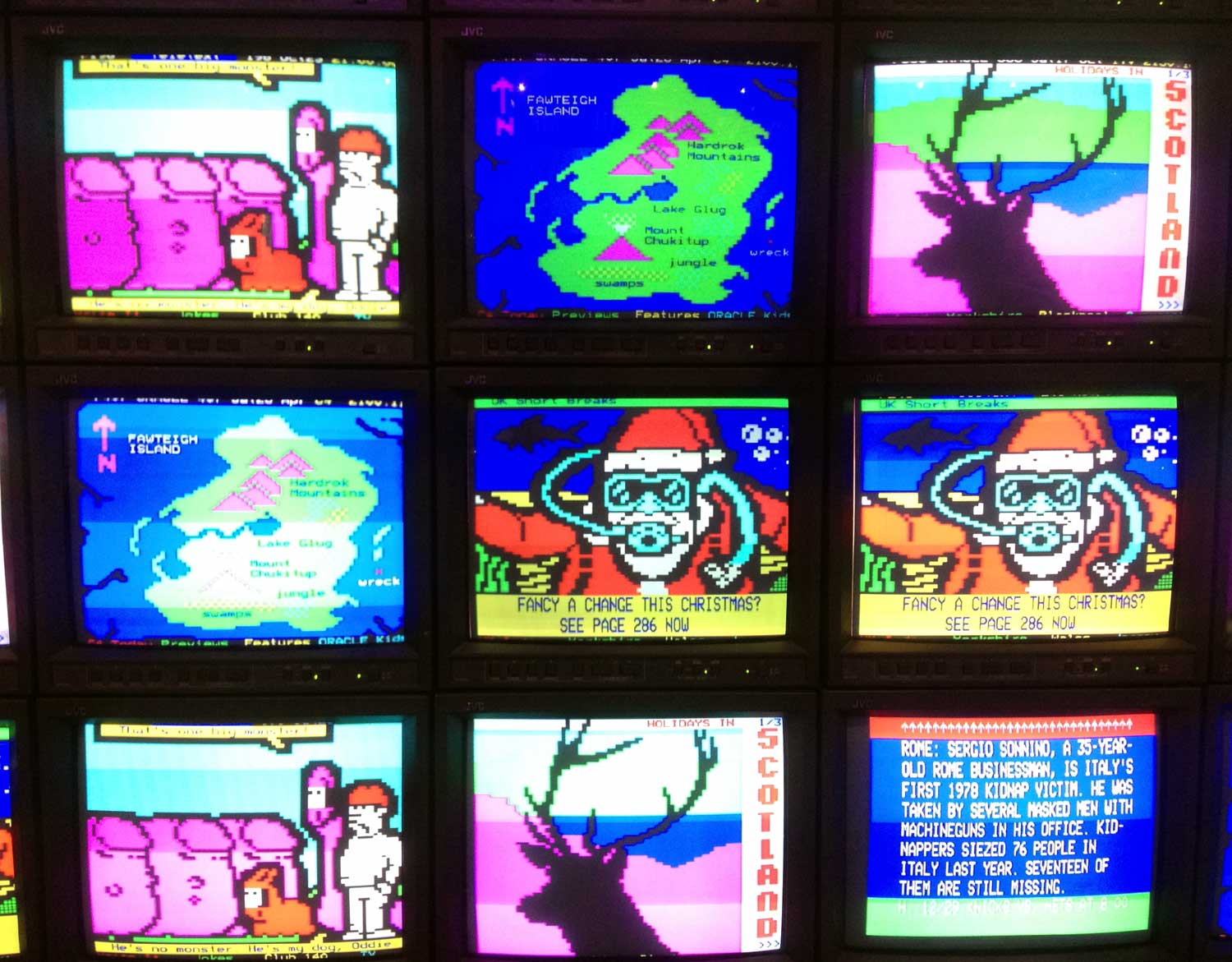

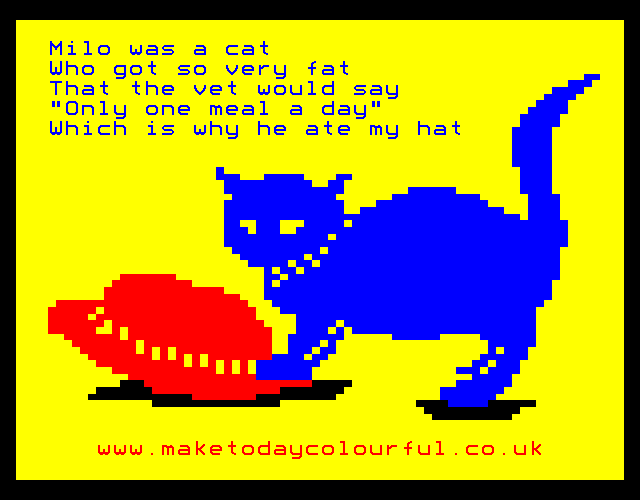

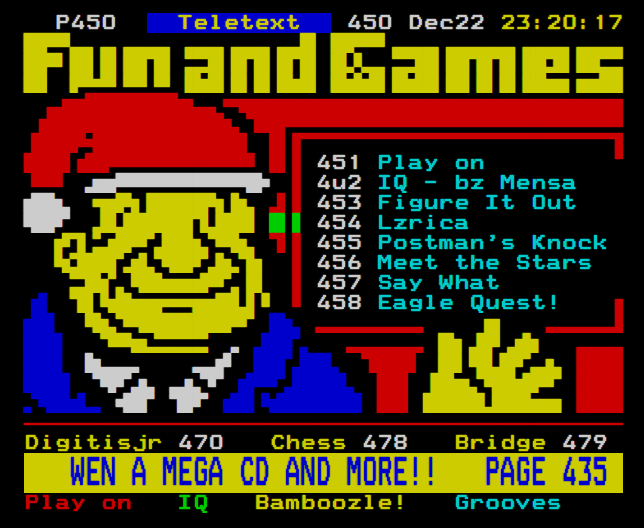

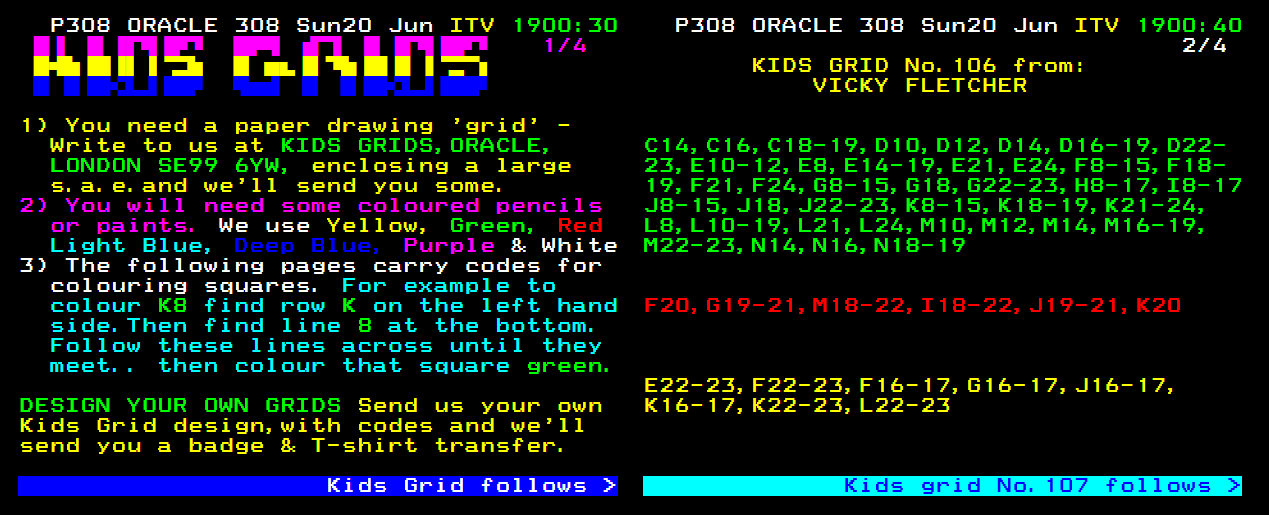

In the late 1970s, ORACLE introduced a pixel art painting-by-numbers game called Kids Grids. These nonograms (also known as Picross) were constructed on a ready-made grid, paper copies of which could be obtained by mail. Viewers submitted their own pixel designs to be converted to grid references, comparable to those used in Battleships, indicating which squares should be filled with which colour.

In time, the ORACLE kids’ jokes page would expand to include teletext artwork illustrating viewer-submitted wisecracks. Kids would also send drawings which would be converted to teletext by a skilled designer.

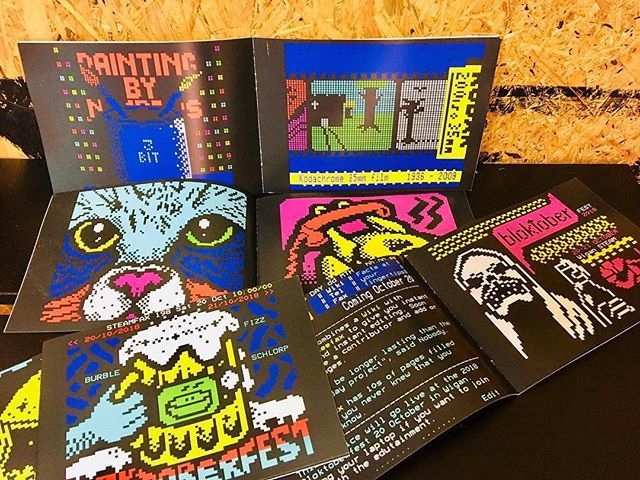

When ORACLE was superseded by Teletext Ltd in 1993, this tradition of digitising younger viewers’ drawings continued on Frame-It. Graphic designer Paul Rose was charged with this task, and over the course of his time at Teletext recreated hundreds of artworks within the teletext canvas.

Art such as this echoes what is believed to be the first artwork created via telecommunication – László Moholy-Nagy’s Telephone Pictures (1922). The artist claimed to have ordered five paintings from a sign factory via telephone, describing exactly where paint should be applied to canvas. Whether he actually did so is debatable, but the mathematical construction and scalability of said markings “highlights the conception of image as transferable data” (MOMA).

One could make a case for children’s digitised doodles being examples of telematic art as they are collaborative pieces between the viewer and teletext editor. However, they are lacking one aspect of the telematic spirit as laid out by Ascott – the element of mass participation.

Revival

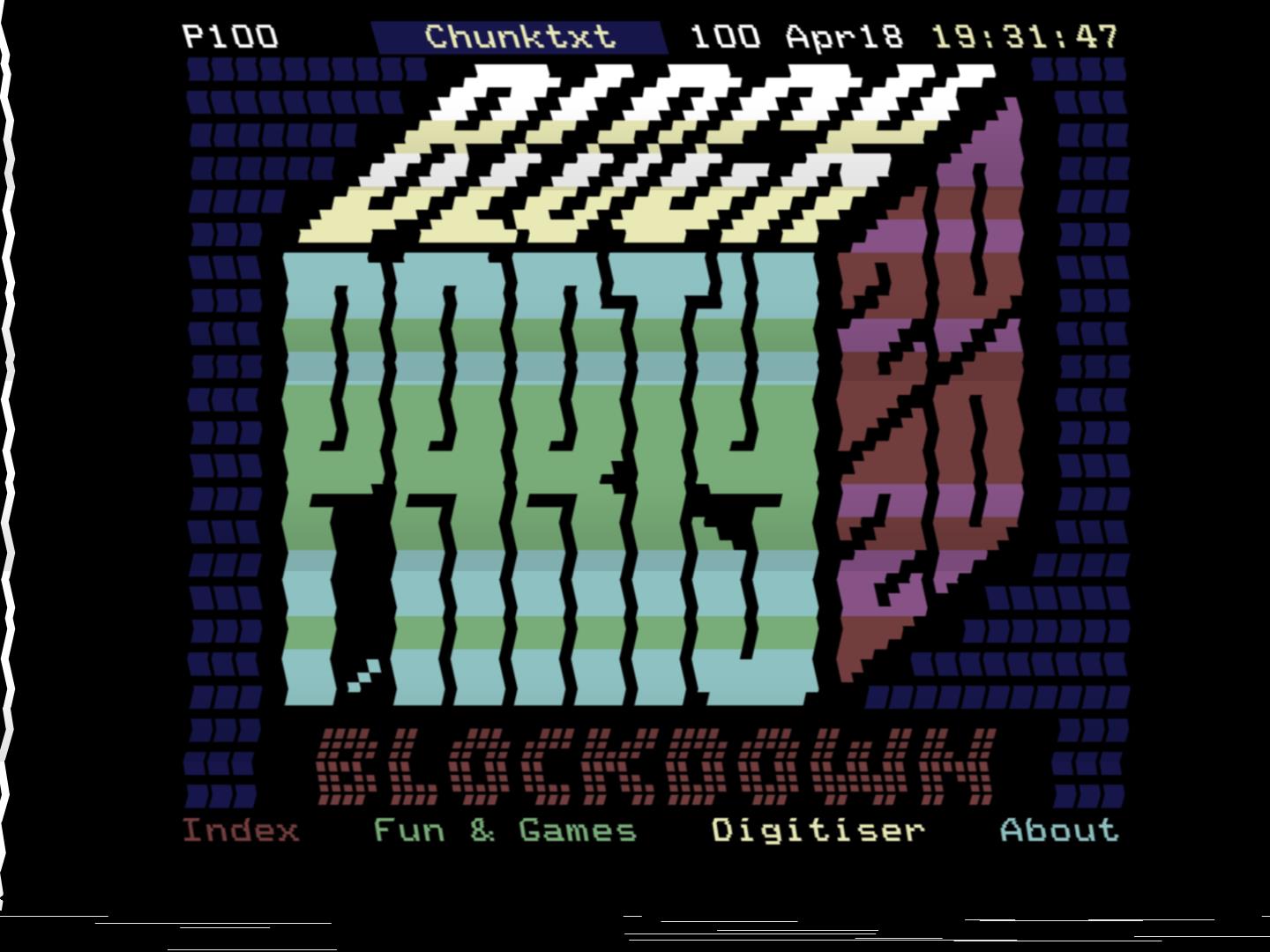

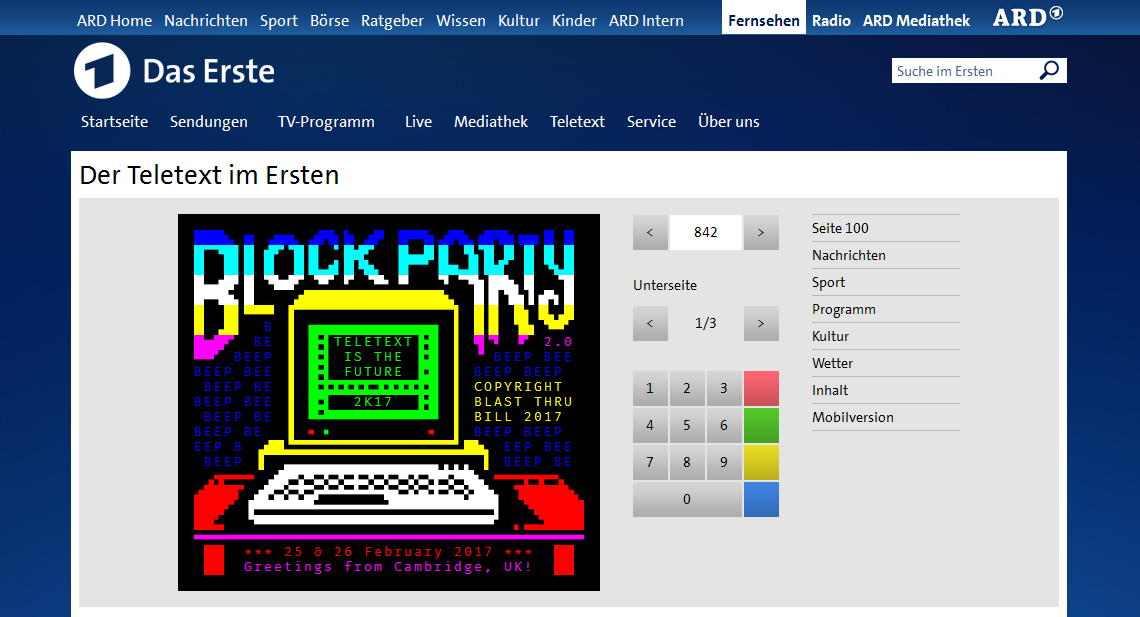

At Teletext Block Party 2017 in Cambridge, six artists collaborated in a game of ‘teletext musical chairs’. Participants were each given five minutes to begin an artwork, then switched places and spent five minutes on another artwork, and so on until the pieces were deemed ‘complete’.

Yet still, those artworks were created by artists in the same locality across a local network. To make the best use of telematics, one would suggest artworks should unite artists in different parts of the world.

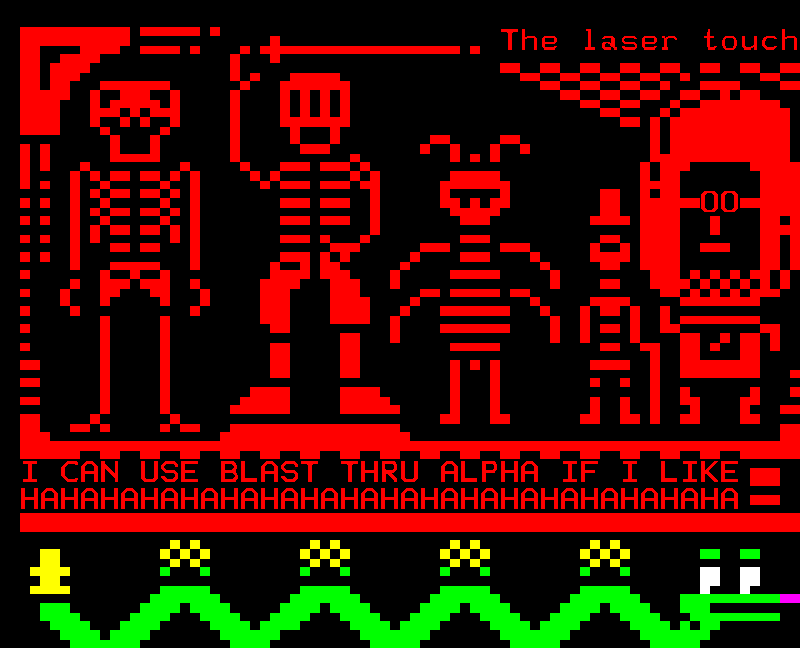

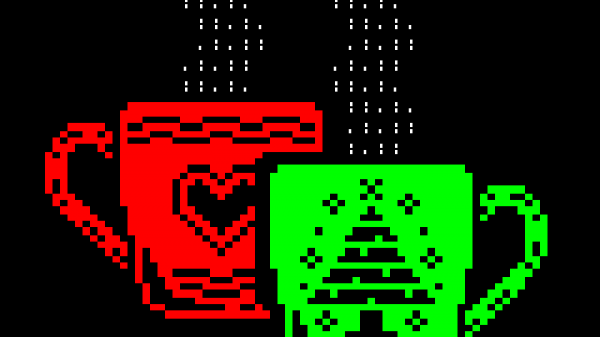

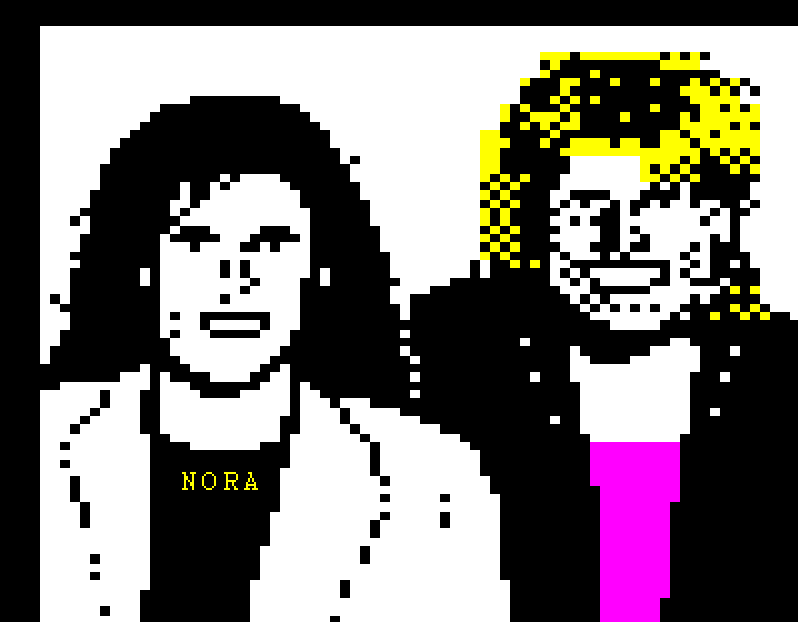

To date, the teletext artworks that most closely resemble traditional telematic art would be the teletext art community’s online collaborative pieces.

The first such exquisite corpse piece on archive is entitled Wigan Special. Created at Teletext Block Party in October 2018, at least eight artists from the UK and possibly other countries (some contributors remained anonymous) simultaneously collaborated to construct an ever-changing experimental artwork featuring pixel representations of a steam train, Mr Men and Shrek.

Wigan Special was facilitated by MUTTLEE, the Multi-User Teletext Live Editing Environment created by former Ceefax engineer Peter Kwan. This allows artists to work on teletext pages remotely and simultaneously, and offers scope for larger collaborative projects in the near future.

Since 2018, teletexters have hosted many more remote art collaborations, a large selection of which can be viewed on the Artfax website. I feel it’s only a matter of time before this format is adapted for the museum environment.

References

- Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness, Roy Ascott, edited and with an essay by Edward A Shanken (2003)

- Teletext in Europe, Hallvard Moe, Hilde Van den Bulck (2016)

- Minitel: Welcome to the Internet, Julien Mailland and Kevin Driscoll (2017)

Recent Comments